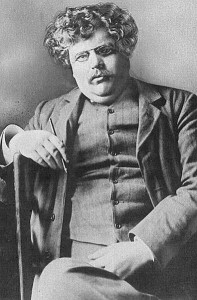

Quoting often does a disservice to the person being quoted, even when the quoter agrees with the point made by the quotee. To illustrate, look at the following text from G.K. Chesterton:

The believers in miracles accept them (rightly or wrongly) because they have evidence for them. The disbelievers in miracles deny them (rightly or wrongly) because they have a doctrine against them. The open, obvious, democratic thing is to believe an old apple-woman when she bears testimony to a miracle, just as you believe an old apple-woman when she bears testimony to a murder. The plain, popular course is to trust the peasant’s word about the ghost exactly as far as you trust the peasant’s word about the landlord. Being a peasant he will probably have a great deal of healthy agnosticism about both.

Still you could fill the British Museum with evidence uttered by the peasant, and given in favour of the ghost. If it comes to human testimony there is a choking cataract of human testimony in favour of the supernatural. If you reject it, you can only mean one of two things. You reject the peasant’s story about the ghost either because the man is a peasant or because the story is a ghost story.

That is, you either deny the main principle of democracy, or you affirm the main principle of materialism — the abstract impossibility of miracle. You have a perfect right to do so; but in that case you are the dogmatist. It is we Christians who accept all actual evidence — it is you rationalists who refuse actual evidence being constrained to do so by your creed.

But I am not constrained by any creed in the matter, and looking impartially into certain miracles of mediaeval and modern times, I have come to the conclusion that they occurred. All argument against these plain facts is always argument in a circle. If I say, “Mediaeval documents attest certain miracles as much as they attest certain battles,” they answer, “But mediaevals were superstitious”; if I want to know in what they were superstitious, the only ultimate answer is that they believed in the miracles. If I say “a peasant saw a ghost,” I am told, “But peasants are so credulous.” If I ask, “Why credulous?” the only answer is — that they see ghosts.

This exact quote has come up recently in two places. First, on the site First Things, and then later on Uncommon Descent. In both cases, the use of the quote goes to criticizing skeptics and materialists, respectively, on how they weigh evidence.

Yet, both uses of the Chesterton quote clip it from the middle of a larger paragraph. Here is the full paragraph:

But among these million facts all flowing one way there is, of course, one question sufficiently solid and separate to be treated briefly, but by itself; I mean the objective occurrence of the supernatural. In another chapter I have indicated the fallacy of the ordinary supposition that the world must be impersonal because it is orderly. A person is just as likely to desire an orderly thing as a disorderly thing. But my own positive conviction that personal creation is more conceivable than material fate, is, I admit, in a sense, undiscussable. I will not call it a faith or an intuition, for those words are mixed up with mere emotion, it is strictly an intellectual conviction; but it is a PRIMARY intellectual conviction like the certainty of self of the good of living. Any one who likes, therefore, may call my belief in God merely mystical; the phrase is not worth fighting about. But my belief that miracles have happened in human history is not a mystical belief at all; I believe in them upon human evidences as I do in the discovery of America. Upon this point there is a simple logical fact that only requires to be stated and cleared up. Somehow or other an extraordinary idea has arisen that the disbelievers in miracles consider them coldly and fairly, while believers in miracles accept them only in connection with some dogma. The fact is quite the other way.

The paragraph comes from the ninth and final chapter of Chesterton’s Orthodoxy: The Romance of Faith, published in 1908. As we see, Chesterton insists that the supernatural is part of objective reality. He goes even further, flatly declaring that one of his primary intellectual positions is that “personal creation is more conceivable than material fate.” In other words, he cannot imagine how the universe and life itself could arise without the intervention of a Creator. Yet, Chesterton does not want to talk about this. With no apparent sense of irony on the dogma that he holds and that holds him, he leads into the part we have already quoted by First Things and Uncommon Descent, the part where Chesterton rails against disbelievers in miracles for being dogmatic.

But Chesterton also claims to have evidence for miracles. What is it? In paragraphs after those we have already seen quoted, he says:

The question of whether miracles ever occur is a question of common sense and of ordinary historical imagination: not of any final physical experiment. One may here surely dismiss that quite brainless piece of pedantry which talks about the need for “scientific conditions” in connection with alleged spiritual phenomena. If we are asking whether a dead soul can communicate with a living it is ludicrous to insist that it shall be under conditions in which no two living souls in their senses would seriously communicate with each other. The fact that ghosts prefer darkness no more disproves the existence of ghosts than the fact that lovers prefer darkness disproves the existence of love. If you choose to say, “I will believe that Miss Brown called her fiancé a periwinkle or, any other endearing term, if she will repeat the word before seventeen psychologists,” then I shall reply, “Very well, if those are your conditions, you will never get the truth, for she certainly will not say it.” It is just as unscientific as it is unphilosophical to be surprised that in an unsympathetic atmosphere certain extraordinary sympathies do not arise. It is as if I said that I could not tell if there was a fog because the air was not clear enough; or as if I insisted on perfect sunlight in order to see a solar eclipse.

As a common-sense conclusion, such as those to which we come about sex or about midnight (well knowing that many details must in their own nature be concealed) I conclude that miracles do happen. I am forced to it by a conspiracy of facts: the fact that the men who encounter elves or angels are not the mystics and the morbid dreamers, but fishermen, farmers, and all men at once coarse and cautious; the fact that we all know men who testify to spiritualistic incidents but are not spiritualists, the fact that science itself admits such things more and more every day. Science will even admit the Ascension if you call it Levitation, and will very likely admit the Resurrection when it has thought of another word for it. I suggest the Regalvanisation. But the strongest of all is the dilemma above mentioned, that these supernatural things are never denied except on the basis either of anti-democracy or of materialist dogmatism — I may say materialist mysticism. The sceptic always takes one of the two positions; either an ordinary man need not be believed, or an extraordinary event must not be believed. For I hope we may dismiss the argument against wonders attempted in the mere recapitulation of frauds, of swindling mediums or trick miracles. That is not an argument at all, good or bad. A false ghost disproves the reality of ghosts exactly as much as a forged banknote disproves the existence of the Bank of England — if anything, it proves its existence.

The first paragraph is polemical, yet the “common sense” eludes me for answering the question of miracles. The reason is that Chesterton at once tries to keep scientific approaches at arm’s length from miracles and claims the supernatural can be verified. In no place in that paragraph does Chesterton offer anything like a positive case that ghosts or souls–dead or alive–can or should exist. It’s very clever to say “It is as if I said that I could not tell if there was a fog because the air was not clear enough,” but where is the obvious follow-up, that we actually do have ways to tell if there is a fog? So, OK, Chesterton, how do you think we can go about telling if there is a ghost or a soul?

The next paragraph has Chesterton in full confidence, concluding that miracles do happen and that he is forced–forced!–to the conclusion by “a conspiracy of facts.” The facts are:

- The men who encounter elves or angels are fishermen, farmers, and all men at once coarse and cautious.

- We all know men who testify to spiritualistic incidents but are not spiritualists.

- Science itself admits such things more and more every day.

- Supernatural things are denied only on the basis either of anti-democracy or of materialist dogmatism.

The first two facts have no bearing on whether miracles happen and should be dismissed. The third point is a puzzle because I cannot tell if Chesterton means that natural occurrences available to science are in fact miracles but re-branded into a secular vernacular. If this is Chesterton’s contention, then what is science and what is nature and what is supernature? The final point is mere rhetoric and certainly not a fact in favor of ghosts, souls, and such.

I said at the outset that quoting does a disservice to the writer being quoted. By going outward from what First Things and Uncommon Descent have quoted, I have sought to reveal even more of Chesterton’s logic and argumentative aims. Yet, I too have done a disservice to Chesterton. Ultimately, the man is attempting to pour personal convictions of Christian faith onto the page. Even the small amount of paragraphs given here show the struggle of these convictions, both the struggle to express them and the struggle to accept them as true.

Can we fault Chesterton for his own dogmatism and baggy sense of factuality? We could, we always could. But I think we can be both sympathetic and critical. We need apologetic and testimonial texts as much as atheist and skeptical ones, and we need to look at how we use and sometimes abuse these texts.