So December 2012 has rolled around at last. Eat, drink and be merry, but make no plans for New Year’s Eve. Apocalypse will arrive on the heels of the winter solstice, either plunging us into global destruction or elevating us to a higher state of being. The Maya predicted it, the I Ching confirmed it, modern prophets wrote best-selling books about it. Mayan scholars and actual Mayans don’t agree, but they are just being killjoys. Deep down, we all love a good prophecy of doom.

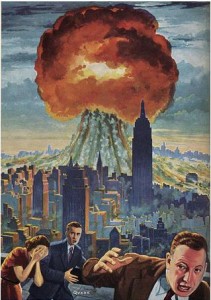

I was reared with a double dose. Born in the fifties, I was part of the first generation to grow up with weapons of mass destruction looming in the background, as familiar and ever-present as the kitchen curtains. At the same time, my family belonged to a fundamentalist church that read current affairs as fulfillments of Bible prophecy, and expected to be raptured out of the snake pit of the world at any moment. As a natural-born atheist, I never knew which would come first, frying in a nuclear holocaust or waving dismally from the ground as my whole family floated up to heaven.

Around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, I started building air-raid shelters out of toy bricks. They were soft red plastic, those bricks, a kind of precursor of Lego, fitting snugly together and textured to look like the real thing. For security reasons, my air-raid shelters always hid behind a tiny fireplace with a false back wall, continued down a narrow tunnel, and ended in a suite holding tiny built-in bunks and shelving, modeled on diagrams in the civil-defense pamphlets. Thus I turned doomsday into playtime, and cut the apocalypse down to size.

In the decades since then, the world has not become a chunk of radioactive slag, nor have the fundamentalist faithful been wafted out of danger. Even so, we have never been without a good supply of doom merchants and prophets, or of dates set for the end of civilization as we know it. Think of the Y2K fiasco. Or think back only as far as last year when, on a certain day in May, the world was billboarded to end in a rolling series of global catastrophes starting at six in the afternoon – and, presumably, 6:30 in Newfoundland. For us, the only explosion was the popping of a champagne cork at 6:01, and the only flames were inside the barbecue. But the failure of a prophecy is soon forgotten, and the world quickly drifts on to the next dire forecast, some of us mocking, some of us just a little worried that the next prophet might actually have a point.

Meantime, popular culture has a soft spot for disaster. In fact, there is some sense in which visions of the end of the world can be fun, particularly ones that are unabashedly imaginary. I have recently, for example, put a fair amount of thought into how we would go about zombie-proofing the farmhouse. Which windows would we brick up? Around which bit of garden would we establish a defensive perimeter? Would it be better to install the chickens in the attic, or set up a zip-line to the barn? At a deeper level, I wrestle with whether I could, in extremis, eat the cats. The answer is that I’d have to catch them first. But this is all a game, and I am not honestly worried about hordes of the living dead shambling about the countryside on a quest for my brains.

But there is another category of apocalypse that is not much fun, even though it is also largely imaginary. This category could be called the purifying apocalypse, where doomsday will be the watershed moment in a grand cosmic plan to purge the wicked and reward the good. The world as we know it, fatally flawed, will explode in a cataclysm of blood and flame, an agonizing labour which will then give birth to a better world: the Kingdom of Heaven, the New Jerusalem, the thousand-year Reich. Painful for the victims that must be immolated, perhaps, but the old phoenix must burn before the new can rise from its ashes. We see this model in the rapture-ready fundamentalists, their multitude of predecessors, and an endless and renewable supply of messianic mini-movements. We see it in the economic world-building of the neocons – the short sharp shock that will magically readjust the market, at the cost of throwing the underclasses to the wolves. We see it in the mad expectations of a Charles Manson or a Jim Jones, in the tragic hopes of the ghost dancers, in Pol Pot’s wielding of a deadly new broom. Historically, this is the most common type of imagined apocalypse, and the most pernicious.

In another class of imagined doomsday, “post-apocalyptic” begins to look more like the movies. The world as we know it ends messily, and then things get worse. There is no grand cosmic plan, no redemption, no Kingdom of Heaven – just a Mad-Max world bombed back to the Stone Age, or ravaged by pandemics, famines, warlords. Meteors hit. The supervolcano explodes. New York dies in myriad imaginative ways. A body part of the Statue of Liberty ends up picturesquely posed on a beach or in a park. Triffids sway in the breeze outside our electrified compounds, while birds swarm our windowsills with murder in their beaks. We apocalypse junkies take a perverse pleasure in this kind of doomsday; like a horror movie or a ghost story, it’s a relatively safe scare, a cheap thrill. It is also strangely satisfying to imagine who might be the survivors in the ensemble cast of the human race. Who would turn out to be a villain, a hero, an idiot? And a bonus: if we ourselves should survive, we would be liberated from the shackles of our routine lives, and never have to pay off our mortgages.

But then there’s the category of real apocalypses, which are not funny at all. These are the ones that provide archaeologists and foreign-aid workers with jobs: real catastrophes, famines, plagues, ecological meltdowns; slow and painful doomsdays spread out over many years; all four horsemen thundering through whole civilizations, leaving nothing behind but confused survivors wandering among archaeological ruins. In fact, the world has ended many times already, on a local scale, and little apocalypses happen every few months. Our historical distinction is to be living in the first era ever when “the world as we know it” covers the entire globe. And that world is changing.

Iexpect our grand apocalypse, if it does come, will be a process, not an event. We can forget all about the Mayan calendar and the Biblical rapture and the supervolcano. We do not need to set dates for doomsday or listen to prophets or try to glimpse the unfolding of a grand plan. Why listen for a bang, when a series of whimpers is already in progress? Perhaps we’ll muddle though, as we have in the past; or perhaps my planning for a zombie apocalypse will come in handy after all. Perhaps the chickens will end up in the attic. The cats, on the other hand – well, no matter what happens, the cats will be safe from me.