There’s been a bit of buzz in my Facebook wall about the upcoming LAWAAG’s “A Woman’s Room Online.” In case you’re unfamiliar, here’s the description courtesy of Skepchick:

The art installation is about online harassment and stalking from the perspective of women, feminist bloggers and journalists who earn at least part of their income from working online.

From what I can see, it looks like a very interesting exhibit; one that, if accurate, paints a fairly dismal portrait of what it’s like to engage in online feminist activism.

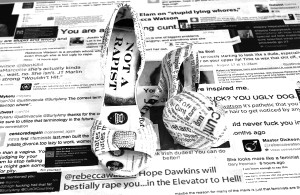

However, I couldn’t help but notice something rather troubling as I perused the pics, particularly this one:

First, it’s definitely a beautiful/horrifying piece of art. The language is strong and the juxtaposition of inflammatory words with the beautiful pumps is definitely jarring. It’s exactly what art should do. But…

My first thought was, “Wow. It must have been really difficult to get all the people involved in this image to sign release forms.”

But then, I began to wonder if, in fact, those involved, are a) aware of that their name/twitter image were involved in this piece and b) gave permission… verbal or written… to take part.

Now, I’ll admit that I’m fairly cautious when it comes to copyright law and fair use. I’m not a lawyer. I don’t play one on television, either. However, I’ve owned a publishing company since ’01 and have had a few tangles with copyright laws through the years. Bottom line?

If I use anyone’s words in any of the books we publish, I always, and I mean ALWAYS have written permission from them. They sign a release form. They’re aware of what words I’m using and why. “Fair use” be damned… it doesn’t matter if the words are from a website, Twitter feed, another book… I get permission. In writing. Every. Time.

Which brings me to the LAWAAG exhibit. I know the artists involved are likely professionals. However, I can’t help but wonder how they got that permission from each and every writer they cite.

Since many of these appear to be Tweets, I figured I’d take a look at Twitter’s copyright policy:

Twitter respects the intellectual property rights of others and expects users of the Services to do the same. We will respond to notices of alleged copyright infringement that comply with applicable law and are properly provided to us. If you believe that your Content has been copied in a way that constitutes copyright infringement, please provide us with the following information: (i) a physical or electronic signature of the copyright owner or a person authorized to act on their behalf; (ii) identification of the copyrighted work claimed to have been infringed; (iii) identification of the material that is claimed to be infringing or to be the subject of infringing activity and that is to be removed or access to which is to be disabled, and information reasonably sufficient to permit us to locate the material; (iv) your contact information, including your address, telephone number, and an email address; (v) a statement by you that you have a good faith belief that use of the material in the manner complained of is not authorized by the copyright owner, its agent, or the law; and (vi) a statement that the information in the notification is accurate, and, under penalty of perjury, that you are authorized to act on behalf of the copyright owner.

Here’s Twitter’s policy on fair use:

Certain uses of copyrighted material may not require the copyright owner’s permission. In the United States, this concept is known as fair use. Some other countries have a similar concept known as fair dealing.

Whether or not a certain use of copyrighted material constitutes a fair use is ultimately determined by a court of law. Courts analyze fair use arguments by looking at four factors:

- The purpose and character of the use.

- How is the original work being used, and is the new use commercial? Transformative uses add something to the original work: commentary, criticism, educational explanation or additional context are a few examples. Transformative, non-commercial uses are more likely to be considered fair use.

- The nature of the copied work.

- What is the copied work itself? Is it factual (example: a record of a historical event) or fictional (example: a novel or Hollywood blockbuster)? Uses of factual works are more likely to be protected.

- The amount and substantiality of the copied work.

- How much of the work was copied? Short excerpts are more likely to be protected than copies of entire copyrighted works, if the use meets other factors as well.

- The effect on the copied work’s value.

- Will the copying harm the potential market for the copyrighted work by effectively creating a substitute or replacement for that work? If so, the use is probably not fair use.

Fair use determinations are made on a case by case basis, and there is no clear formula to determine whether a use may be found to be fair. If you are unsure whether a particular use of copyrighted work might be a fair use, you may want to seek legal advice. Twitter is unable to advise whether your use may be protected or not.

For more information on fair use:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_use

https://ilt.eff.org/index.php/Copyright:_Fair_Use

OK. But are individual tweets protected under copyright law? It appears as though the definitive answer is “it depends.” According to Art Law Journal:

Copyright protection exists the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form. But copyright does not protect facts, ideas, systems, or methods of operation, although it may protect the way these things are expressed.

In the EU, the copyright situation is more clear cut.

Are tweets protected by copyright? Well, it would seem that under EU law – or rather CJEU understanding of EU law – the answer should be in the affirmative. In its 2009 decision in Infopaq, the court found that copyright may subsist in a text extract of 11 words and – more in general – it subsists whenever a work is its author’s own intellectual creation.

That said, it appears as though the images, the avatars, may be protected by copyright… assuming the Twitter user had permission to use the image and/or created it themselves.

This exhibit raises some interesting questions in my mind. I suppose, in a perfect world, artists wouldn’t have to worry about using other people’s possibly copyrighted material in their work. That said, I can’t help but wonder if those included in that particular installation know their words, names, and/or image are displayed up front and center.

Finally, does the matter of possible copyright infringement matter to the broader skeptic community? How about the inflammatory tweets? Is this how we present ourselves to the broader community? Is naming and shaming a viable tactic to persuade a more rational discourse? Is the naming and shaming tactic presumably used here worth the possible legal liability? Is CFI (from what I can tell, they’re somehow involved in this project) aware of these issues?

I don’t know.

Perhaps I’m just an overcautious stick in the mud who goes to great lengths to avoid lawsuits, C&Ds, and the like. But that’s just me.

I’d love to know what other people think…